‘Blue is for boys and pink is for girls’- I’m sure you’ve heard that one before, as have I. So much so, that somewhere around my early teens, when I decided I was going to be a strong and independent girl who could match any boy- I also decided to ditch the rosy hue, along with everything else that felt overtly feminine. That’s also why, to this day, I don’t know how to cook (sorry, mom). But as a fashion girl, my giving up the ‘girliest’ colour on the planet was a strong sign of protest, at least in my head. It was a refusal to be boxed in by society’s pink-coded expectations.

And so, for most of my teens and 20s, you wouldn’t catch me dead in a bubblegum tee or a flouncy pink dress. No millennial blush, no flamingo, no fuchsia. In my head, pink was too girly, too loud, too obvious. In my mind, wearing pink was like raising a flag that screamed, ‘I’m feminine and probably not great at math.’ But here’s the plot twist- I was feminine, and I was great at math. So, I settled somewhere safe with a compromise called peach.

It wasn’t until the recent Barbie obsession that fashion had made me crave a good pink fashion moment. I somehow rode out Barbie fever, managing to not fully indulge- but pink has not been out of sight ever since, coming back as bubblegumpink, hot pink and the most recent- millennial pink. Finally, I knew it was time for me to introspect. Surely, 30-year-old me had a different opinion about pink and all that it entailed. Was I really going to avoid a colour I’d love to wear because society told me it was too feminine? I had already grown into the strong independent woman I wanted to be as a young girl, and from that experience, I knew colour had nothing to do with independence. Turns out, my personal pink aversion had a history far beyond my closet.

The Evolution of Pink: From Royalty to the Toy Aisle

Pink wasn’t always ‘for girls.’ In fact, back in the 18th century, it was considered a strong, bold colour often worn by men in Europe. In fact, King Louis XV of France and other members of European courts frequently wore rose-toned garments. In Rococo art and fashion, pink was associated with elegance and sophistication rather than gender.

In the early 1900s, there was no universal rule for dressing babies in pink or blue. Many department stores and parenting manuals actually suggested pink for boys and blue for girls. Pink was seen as a stronger, more decided colour, while blue was delicate and dainty, thought more appropriate for girls. This preference varied by region, retailer, and publication.

Image Source: Pinterest

The shift happened slowly but firmly. By the 1940s and 1950s, manufacturers began to standardise baby clothes by gender to sell more products. Post-World War II, traditional gender roles were reinforced in advertising, and pink became associated with idealised domestic femininity. In 1953, First Lady Mamie Eisenhower wore a pink gown to her husband’s inauguration and was often seen in ‘Mamie Pink.’ Her style helped popularise the colour as a symbol of grace and traditional womanhood. Hollywood and fashion followed suit with Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes made the phrase ‘Think Pink’ iconic.

By the 1980s, with increasing market segmentation, pink dominated toys, clothes, and media targeted at girls. Mattel’s Barbie brand, launched in 1959, leaned heavily into pink marketing by the 1980s, becoming synonymous with the colour. Pink aisles in toy stores became the norm, and the colour's association with girlhood grew stronger.

Image Source: mirror.co.uk

Feminist Rejection vs. Reclamation

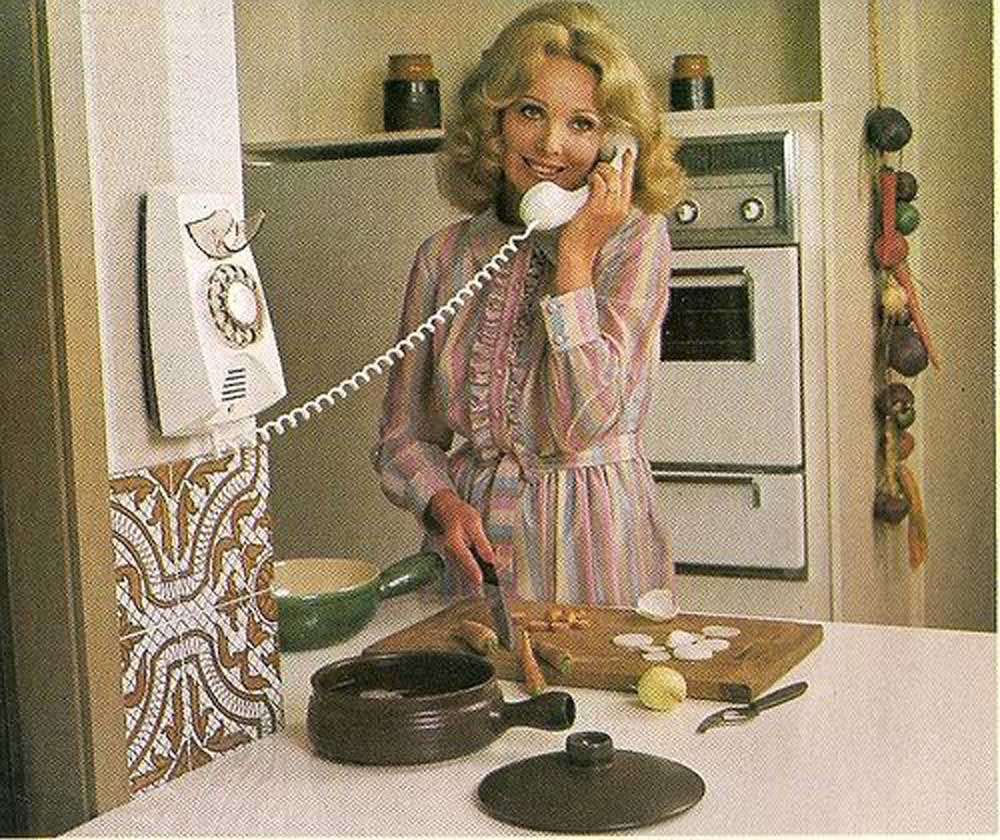

As second-wave feminism surged in the 1970s, pink began to symbolise everything women wanted to distance themselves from: conformity, domesticity, fragility, and a beauty standard built by and for the male gaze. The pastel palette, especially pink, was tied to the image of the ideal housewife- gentle, passive, decorative. In professional settings, women swapped pinks and pastels for neutrals like navy, grey, and black to be taken seriously in male-dominated workplaces.

Image Source: Seventies Housewife

As psychologist Dr. Carolyn Mair notes in The Psychology of Fashion, colour choices are often linked to power perception. Bold, saturated colours were viewed as less ‘serious’, a bias that disadvantaged women trying to climb corporate ladders.

But as feminism evolved, so did the narrative. Why should pink, a colour historically forced onto women, also be something we’re ashamed of?

In the 21st century, pink re-emerged- not as a default, but as a deliberate choice. Women and gender-diverse folks began wearing pink on their own terms. It wasn’t about blending in. It was about standing out.

Image Source: Concreteplayground.com

Riot Grrrl culture, Punk and Grunge in the ’90s paired girlish aesthetics with aggressive punk attitudes- pink hair and combat boots were part of the rebellion.

Cultural Moments That Reshaped Pink

Image Source: Squarespace.cdn.com, Instagram/metgalaofficial_

Barbiecore (thank you, Greta Gerwig): With the 2023 Barbie film came a tidal wave of unapologetic hot pink, reminding us that girliness can be both fun and powerful.

Millennial Pink: The muted, Instagrammable blush that defined an entire generation’s aesthetic- quiet, versatile, and less threatening than its bolder predecessor.

Gen Z Pink: Loud, ironic, and genderless. Think pink hair, oversized hoodies, and Crocs. It’s not about being pretty, it’s about making a statement.

In each of these moments, pink became a tool of identity expression, sometimes wielded with pride, sometimes with a wink.

What Wearing Pink Means Today

Today, wearing pink is complicated, but also freeing. For some, it’s an act of reclaiming femininity. For others, it’s about pushing back against rigid gender norms. Sometimes it’s just a colour you like. And that’s the point.

Pink no longer needs to carry the weight of societal expectations, unless you want it to. Whether you're in a Barbiecore blazer or a rani pink kurta, the meaning is yours to define.

Image Source: Instagram/aliaabhatt

The Bottom Line?

Pink is not inherently oppressive, nor is it automatically empowering. Like any colour, its symbolism is shaped by context, culture, and personal choice. The key is asking: Are you wearing pink because you want to- or because you feel like you have to?

And if it’s the former- rock that rani pink with pride.